The Problem

Educational attainment for children has lifelong implications for social and economic well-being, health, and other outcomes of individuals (Bonnie et al., 2015).

However, a growing body of empirical research suggests that first-generation immigrant secondary students are not receiving the intellectual, social, and emotional support they need to lead successful, fulfilling lives in Canada (Areepattamannil & Berinderjeet, 2013; Busby & Corak, 2014; Kirova, 2001; Lara & Volante, 2018; Vitoroulis & Georgiades, 2017).

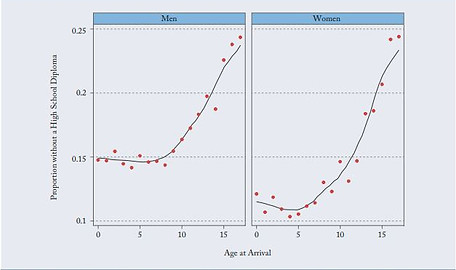

Moreover, Busby & Corak (2014) found that immigrant children who settle in Canada after the age of nine are more likely to drop out of school than non-immigrants and immigrants who settle earlier (see Figure 1).

With more than a quarter of all Canadian children under the age of twenty born outside Canada (Statistics Canada, 2017), how prepared are secondary schools to ensure that these students adapt well and to their full potential?

Figure 1.

Note: This graph was taken from Busby, C., & Corak, M. (2014). Don't forget the kids: How immigrant policy can help immigrants' children. C.D. Howe Institute E-brief, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2436955.

Definitions

Immigrant student is used throughout this site as an umbrella term that refers to any student under 18 years of age who enters a classroom (either permanently or temporarily) and has been born in a country where the culture and language spoken differs from the dominant culture and language of their host country (Bartlett, 2005).

Culture is the shared patterns of a society that are transmitted over time through generations (Schineller & Rummell, 2019).

Ethnic background refers to the origins of a group of individuals who have a shared culture, nationality, history, or religion (Schineller & Rummell, 2019).

Literature Review

The existing literature that documents immigrant student integration and academic achievement in Canada reveals three patterns that prevent certain students from realizing their potential:

1) Language deficiency - Immigrant youth from non-English or French-speaking countries with limited proficiency in those languages tend to experience lower academic achievement and attainment levels in Canada (Areepattamannil & Berinderjeet, 2013).

2) Bullying and psychological well-being - Immigrant youth are at higher risk of bullying and other forms of discrimination based on their race, colour, ethnicity, religion, and other identity characteristics (Vitoroulis & Georgiades, 2017; Wu & Penning, 2015, as cited in Stick et al., 2021). Despite the need for emotional or psychological support, a significant proportion of these students do not seek help for various reasons, including poor understanding of mental health services, fear of the stigma associated with mental health treatment, or lack of access to support resources (Vitoroulis & Georgiades, 2017).

3) Feelings of isolation and social exclusion - Canadian schools and teachers tend to practice ethnocentric as opposed to multicultural education (Kirova, 2001; Lara & Volante, 2018). Despite teachers' best intentions, they may overlook cultural differences between students and “apply universal values and principles to their educational practices” (Bayles, 2009, p. 110, as cited in Lara & Volante, 2018). A lack of cultural awareness and response to differences can cause immigrant students’ to develop poor mental health (e.g., silent anxiety), which can have significant adverse effects on their behaviour both in and out of the classroom (Kirova, 2001; Lara & Volante, 2018; Wu & Penning, 2015, as cited in Stick et al., 2021).

As immigrant students continue to be a growing demographic within Canadian secondary school systems, educators, school administrators, and policymakers must find solutions that not only support language development but also facilitate positive social interactions to enhance their social and emotional well-being.

Overview

COMPASS was designed to help immigrant secondary students (ages 12-18) overcome social and academic obstacles by giving them access to culturally-centered guidance from a network of adult immigrants from various fields and industries.

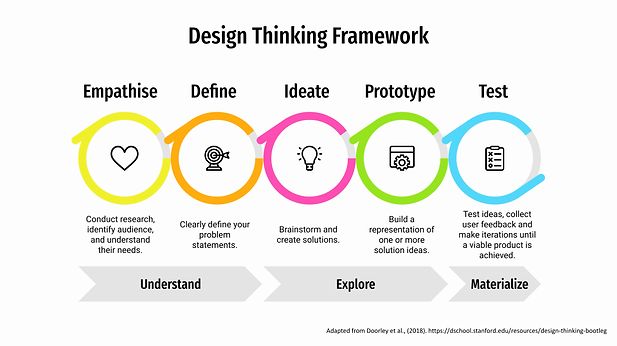

Completed in July 2022 as part of LRNT527's Creating Digital Learning Resources 9-Week course, this was an in-depth exploration of Design Thinking methods, where my role was to lead the entire product design life-cycle using the five phases of the Design Thinking framework (see Figure 2) — empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and test — to ensure that the stakeholders of this project were kept at the heart of the process (Doorley et al., 2018).

Figure 2.

This project evolved from a semi-structured interview with Marius, a 15-year-old immigrant secondary student from Romania struggling to find support during his transition to Canada and a new educational system. With his frustrations in mind, I brainstormed solutions that address the gaps that impede the success of new arrivals in secondary schools across Canada and highlight the importance of learning about their new country and how they can make Canada a better place.

The findings highlight the necessity of a technological intervention that can provide educational tailored support to immigrant secondary students inside and outside the classroom and the significance of connecting these students with mentors that can meet their core needs that many schools may not be equipped to address.

Design Thinking Framework

Empathize

-

Secondary research

-

Primary research

-

Empathy map

-

Persona creation

Define

-

Redefine problem statement

-

Hypothesis

-

Reframe the problem with "How might we" statement

Ideate

-

Brainstorm ideas

-

Select a solution

Prototype

-

Pedagogical and technical considerations

-

Interactions

-

Paper sketches

.

Test

-

Create prototype

-

Usability testing

-

Iterate based on findings

EMPATHIZE

What are the needs of the people we are solving for?

After an initial round of secondary research, I took on a beginner’s mindset to free myself from old design habits and biased assumptions (Morris, 2018). To learn more about the challenges faced by immigrant secondary students and the effectiveness of existing support systems, ethnographic research in the form of semi-structured interviews was carried out to understand the situation better from multiple perspectives (i.e., both student and teacher).

Next, the qualitative data collected from the stakeholder interviews were used to create an empathy map (see Figure 3) and user persona (see Figure 4) for my target group (immigrant secondary students who came to Canada after age 9).

These design tools allowed me to consolidate and visualize information to identify critical challenges and understand the gravity of the situation I am attempting to solve (Doorley et al., 2018).

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

.png)

DEFINE

What problem are we trying to solve?

As I reflected on stakeholder feedback, I organized data into the following two themes:

-

Need for guidance - Immigrant students experience various challenges (both at home and at school) that impact their ability to adapt to a new culture (while also trying to retain their own) and achieve academic success. This presents the need for individualized guidance for these learners.

-

Lack of support - Some high schools across Canada have a critical shortage of mentoring opportunities for immigrant students, creating a gap that limits their academic success. This presents a problem around current and future access to support for these learners.

After thoroughly understanding the perspective of my target group and identifying their pain points, I selected one area for improvement out of the many issues raised in this process, because I believe it is the most important (as well as most feasible) to address: “Most immigrant secondary students have insufficient access to meaningful and sustained support resources to ensure they adapt well and to their full potential within their host schools.”

Next, I created a “How might we?” statement: “How might we make meaningful and sustained support more accessible to immigrant secondary students?”

Rewording my POP helped me turn the problem into an opportunity and allowed me to stay open to multiple potential solutions.

IDEATE

What solutions can we explore?

Using the student persona generated in the empathy phase as an extension of myself (Doorley et al., 2018), I began to brainstorm solutions for the “How might we?” statement by typing out ideas that came to mind without judgment (see Figure 5).

After considering a few viable solutions, I created a mobile application (app) that helps connect young immigrant students with older immigrant students and experts across Canada.

This idea was inspired by Crul and Schneider’s (2014) research, which found that European mentorship initiatives paired younger immigrants with older immigrants, improved educational outcomes, and promoted resilience among youths.

Figure 5.

PROTOTYPE

How will we create the solution?

Now with a potential solution in mind — virtual mentoring through a mobile application — it was necessary to consider both the pedagogical and technical aspects of its design.

To address the social and personal aspects of learning, the Community of Inquiry (COI) framework (Garrison et al., 2000) was used to inform my decision-making regarding the features of the app (for more information on the COI framework, see the "How it works?" page).

Interactions

I created a site map (see Figure 6) to organize and structure information for the app to establish the hierarchy of the screens/pages to ensure the user can perform all the necessary functions (Breton et al., 2022). Then, I developed a user flow chart (see Figure 7) to outline the core task flow: How to find a mentor.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

User flow for finding a mentor

The interactive tasks of the app shown in the user flow chart above include:

-

Sign in/Sign up on the landing page

-

Accept or reject mentor recommendations

-

Find mentors using the search filter

-

Sort tags

-

Browse mentor profiles on the results page

-

Select mentor

-

View mentor details

-

Send mentor request

-

Mentor request complete

-

Confirm match

After the student has set their preferences, COMPASS uses additional information collected from mentor and student profiles and results from an on-boarding questionnaire to pair mentor and student once a compatible match has been found. However, when a match is found, the student must either 'accept' or 'ignore' the match before the mentor and student relationship can proceed.

Sketches

With the app's basic layout in mind, I sketched a paper prototype (see Figure 8) to give concrete form to my abstract ideas (Doorley et al., 2018) and visualize the user flow identified previously. Hand-sketching the prototype made iterations much easier.

Figure 8.

.png)

.png)

TEST

How will we test the efficacy of the prototype?

The final step is to test the prototype on potential users. After going through the user flow experience using the paper prototype, I gained a better understanding of how users would interact with the app. I made a few minor iterations and went on to design digital wireframes using Canva. Based on the digital wireframes in Figure 9, a prototype was created (see video below).

Figure 9.

.png)

Reflection

Before embarking on this design journey, I was familiar with the design thinking process and recognized it as a powerful tool for solving real-world problems.

The Problem of Practice (POP) stated in this case study was that most newcomer immigrant secondary students have insufficient access to meaningful and sustained support resources to ensure they adapt well and to their full potential within their host schools.

Of course, transitioning to a new country and school can be intimidating for anyone. Still, this change can be particularly challenging for newcomer students, aged 9 to 18, who come to Canada with little or no knowledge of the language and culture of their host country. These students need support from people who understand their struggles and can offer practical, culturally-centered advice to overcome these unique difficulties.

The creation of COMPASS — a mobile mentoring app that helps connect young immigrant students with older immigrant students and experts across Canada — was a massive project. Indeed, there is a lot to consider when designing and developing a mobile app. For one, I needed to ensure that my solution fulfilled the users' needs. Then, I had to ensure that navigating the app was as simple and self-descriptive as possible, so users could quickly find information. Once I had the basic layout designed, I had to consider adding features that evoke positive emotions to keep the users motivated to use the app. Finally, I needed to outline how I would protect personally identifying data collected by the app, so that users could trust my product.

Takeaways and what I would do differently

Working fully through this project taught me the importance of trying to think intentionally about every element of the project and how it can contribute to the end result. Indeed, there is still much more to be done before COMPASS becomes a viable product, but overall I am pleased with the result. My only regret throughout this design challenge was my limited ability to collaborate with multiple stakeholders due to project time constraints. If I had more time, I would have liked to better adhere to WCAG standards and engage with a larger group to gain more diverse insights and perspectives on the design features and usability of the app.

If you have questions about COMPASS or the design process outlined here, contact me below.